|

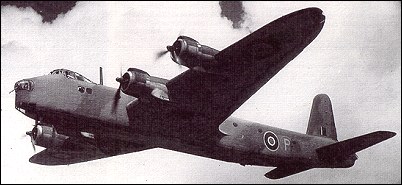

| The Stirling's design was based on Air Ministry Specification B.12/36. It was the first of the large four-engined bombers to go into service with the RAF. The original layout of the bomber was tried out by the construction of a half-scale model fitted with four 97kW Pobjoy engines. Flying trials with this proved the feasibility of the design, which included several novel and previously untried features.

The prototype Stirling (with four Bristol Hercules II engines) flew for the first time on 14 May 1939. This aircraft crashed on landing after its maiden flight, but a second prototype was completed and was flying in. the autumn of 1939. Deliveries of production aircraft to the RAF began in August 1940, the early aircraft being built by the parent company. An organisation system of dispersal was soon put into operation, whereby the main components were built in more than 20 different factories.

The first production version for the RAF was the Stirling I powered by four 1185kW Bristol Hercules XI radial engines and without a dorsal turret fitted. Mk Is were first used in action on the night of 10-11 February 1941. The Stirling II, only a few of which were completed, was a conversion of the Mk I with Wright R-2600-A5B Cyclone engines. The Mk III had four 1,230kW Bristol Hercules XVI engines and featured a mid-upper turret. From 1943, when the Stirling was no longer a suitable bomber, many were fitted for glider towing (Horsa glider).

Unlike the Mk III, the Stirling IV was produced from new as a long-range troop transport and glider tug, the nose and upper turrets being removed and replaced by fairings, although the four-gun tail turret was retained. Up to 24 paratroops or 34 airborne troops could be carried. The final version of the Stirling was the Mk V, an unarmed military transport and freighter with a redesigned nose. Total production of the Stirling - the Mk III of which was the major variant - was about 2,380.

FACTS AND FIGURES © The Stirling used a cut-down

version of the wing from the

Sunderland flying boat, reduced

by over 4m in span. © The complicated undercarriage

legs were very long to increase the

wing incidence and reduce the

take-off run. The length and

design of the legs contributed to

many accidents. © The size of the bomb bay

restricted the weapons that could

be carried to nothing larger than

907kg bombs.

| MODEL | Stirling Mk III |

| CREW | 7-8 |

| ENGINE | 4 x Bristol Hercules XVI, 1230kW |

| WEIGHTS |

| Take-off weight | 31751 kg | 69999 lb |

| Empty weight | 19595 kg | 43200 lb |

| DIMENSIONS |

| Wingspan | 30.2 m | 99 ft 1 in |

| Length | 26.59 m | 87 ft 3 in |

| Height | 6.93 m | 23 ft 9 in |

| Wing area | 135.63 m2 | 1459.91 sq ft |

| PERFORMANCE |

| Max. speed | 435 km/h | 270 mph |

| Ceiling | 5180 m | 17000 ft |

| Range w/max payload | 950 km | 590 miles |

| ARMAMENT | 8 x 7.7mm machine-guns, 6350kg of bombs |

| A three-view drawing (792 x 1186) |

| Anonymous, 12.01.2024 14:17 Hi reply | | Jack Cole, e-mail, 21.03.2014 07:14 I totally agree with all the comments regarding the Stirling's performance being compromised by air ministry requirements, but would like to make a couple of points. As someone else has pointed out, hanger widths at that time were 120 feet, yet it is a fact that the spec called for span below 100 feet. The earlier marks of Halifax were built to comply with this and suffered accordingly.

Roy Chadwick, when designing the Lancaster (or rather when converting the Manchester) was subject to the same limitation, but chose to ignore it, and in fact when the Lancaster was accepted by the Air Ministry they made a typically civil service comment along the lines of "This is a satisfactory aircraft, but we deplore the way it was made so"

In fact the very fact that the Sterling was the first four engined heavy bomber produced was it's downfall, the Halifax also suffered in a similar way, but in the end was modified into a superior aircraft in nearly all respects (apart from Harris's yardstick, bomb load) than the Lancaster.

The fact the Sterling, and indeed the Halifax could only carry 2000lb maximum bombs was again down to the civil servants, as the thinking was at the time that a stick of smaller bombs would be more effective than a single large one. Again Chadwick had different ideas.

Finally, I believe that the length of the Sterling was due to the fact that they used the top half of the Sunderlands fuselage to cut down on development time. reply | | VinceReeves, 05.03.2013 21:54 The Stirling put in a reasonable performance as a bomber. It wasn't a resounding success, but it wasn't an abject failure, either.

It performed plenty of useful secondary roles afterwards, confirming its airworthiness. reply | | Chris Marco, e-mail, 06.09.2012 14:43 It's a shame none exist. I design Model aircraft and am trying to locate information on the Short Sterling landing gear, such as a drawing is difficult. If anyone has an isometric of the landing gear mechanism I would appreciate a copy. reply | |

| | Klaatu83, e-mail, 18.06.2012 01:31 The Stirling has come in for a great deal of criticism over the years, especially in comparison with the later Lancaster and Halifax bombers. However, most of the faults that have been found with the Sterling were directly attributable to the British Air Ministry specification around which it was designed, rather than to the designers and manufacturers. For example, the reason the Lancaster and Halifax had larger bomb bays was that the Air Ministry insisted that they be designed to carry a pair of torpedoes internally, a stipulation they did not make when ordering the earlier Stirling. The Stirling specification only called for the carriage of bombs of up to 2,000 pounds, which it did. Likewise, the Air Ministry also insisted that the Stirling's wings be short enough to fit into existing hangers, a condition which they did not make with the later bombers. It was also the Air Ministry that insisted that the angle of attack of the Stirling's wings be increased to 3 degrees, which was why the landing gear ended up so long and awkward. essentially, Shorts gave the Air Ministry exactly the airplane they asked for. reply | | Stephen Gash, e-mail, 13.03.2011 21:47 If keeping the wingspan short was so essential then one wonders why they didn't try folding wingtips. I read somewhere that the Halifax originally had slats, but the Air Ministry wanted balloon cable-cutters along the leading edge! The history of aircraft procurement in Britain is lamentable. reply |

| Ben Beekman, e-mail, 07.02.2011 22:49 I had some comments on this aircraft but mistakenly put them on the Short S.31 (half-scale model) page instead.

Sorry. reply | | Barry, 07.01.2011 17:08 Isn't it strange or just typical that by the time the Lancaster and Halifax entered service the hangars were large enough. One wonders what these numpties use for brain cells, and what is particularly galling is that their ilk are still in control today.

Anyway because of the design this heavy bomber could not carry any bomb larger than 2000lb! It was extremely difficult to take off and land needing the flight engineer's help with the throttles, in other words an aeroplane that could not take off single handedly. It's service ceiling was limited and Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris could not wait to get shot of them. However, it is said that once they were in the sky they were a joy to fly. reply | | jules, e-mail, 10.12.2010 12:59 Congrats to Short for bringing this heavy on-line so quick. Shame about the weak undercarriage and low ceiling but it had a remarkable turning ability which saved many crews lives when evading attack and searchlights reply | | martin smith, e-mail, 15.08.2010 16:51 The then hangers were 120` openings,it was just a bad design for a land based aircraft. reply | | Barrett, e-mail, 28.07.2009 18:05 @ Leo

They were probably trying to fit as many bombs as possible in the fuselage and max out hangar space. Not a performance-oriented philosophy lol reply | | leo rudnicki, e-mail, 24.04.2009 03:12 The wingspan was kept under 100 ft to fit standard RAF hangars, standard Air Ministry muddleheaded thinking, but why was the fuselage so much longer (17 ft) than Lanc /Halifax? A shorter fuselage would have precluded the need for the ridiculous undercarriage and the need for oxygen in a parked aircraft. This Short was too long. reply | | EMBER, e-mail, 23.12.2007 00:24 STIRLING'S LANDING GEAR WERE VERY TALL. THIS GAVE THE PLANE A 30-DEGREE UP ON THE GROUND, THIS WAS FOR SHORT TAKE-OFF, BUT THE GEAR RETRACKTORS WERE NOT SUTIBLE FOR LIFTING THIS HEAVY LOAD. reply |

|

Do you have any comments?

|

|

COMPANY

PROFILE

All the World's Rotorcraft

|

Hi

reply